Freeport McMoRan’s 80-square mile Morenci mine, the largest copper mine in North America, has laid waste to two important family historical markets: the Shannon Mine in Metcalf that made William Boyce Thompson a millionaire and the family home where Julius Kruttschnitt entertained family guests after the birth of his first daughter, Meanie. The recent discovery, which should have been discovered long ago, would have to go down as one of the biggest disappointments in Thompson Family history.

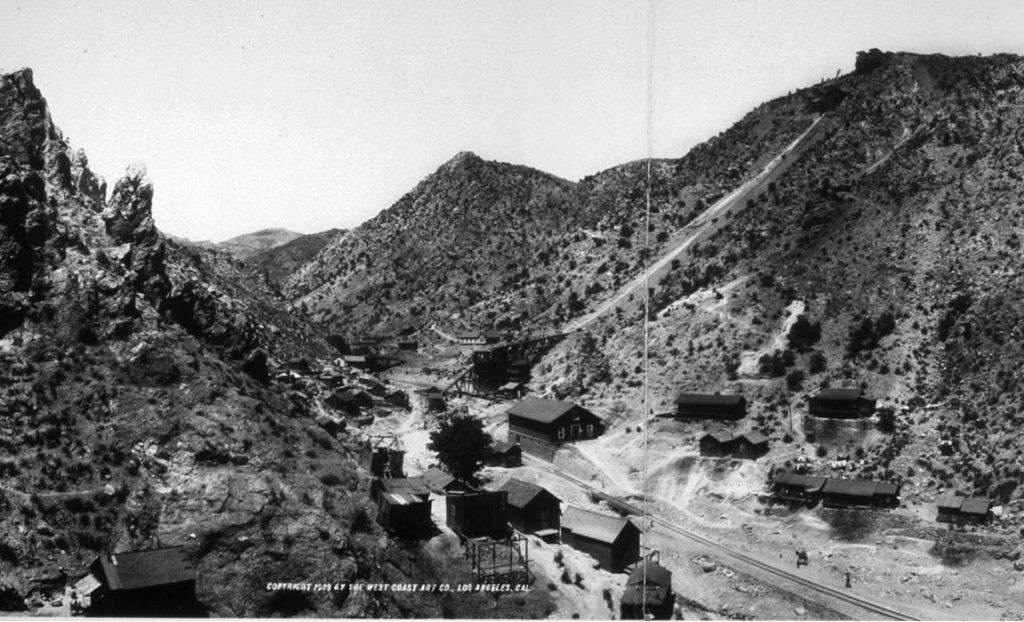

The open pit mine at Morenci is really, really big. It cuts a huge scar into the otherwise picturesque Arizona high country as you approach from the Southwest. The mine is so big that it ate up the original town of Morenci, which disappeared into an open pit in the 1960s. It took with it the fabulous Morenci hotel where my family, the Kruttschnitts and Pickerings, probably stayed while in town. The mine also subsumed the town of Metcalf, Arizona, where William Boyce Thompson ran his underground mine from (1899 to 1929). In fact, the entire Chase Creek Valley, where mining operations once scaled the hills, is no more.

That said, a few fragments from Thompson’s time remain, including the environmental wasteland created by the Shannon company’s smelter in Clifton, the only one of the original three towns from the turn of the 20th century that has survived mining progress. According to a recent state environmental review, the black, charred ground formerly supported smelting operations contains toxic metals that no one should touch. Thankfully, caps and drainage systems prevent most exposure from the mining tailings. “There is little to no health risk unless there is contact with skin or ingestion of contaminated soil,” reported the state, which annually inspects the site and engineering controls and after significant rain events.

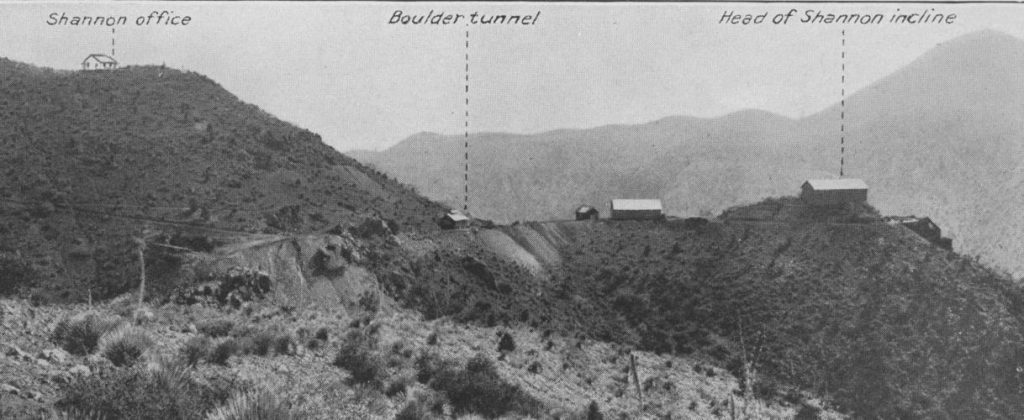

It’s hard not to get nostalgic about all these places that are no more. The Greenlee Country Historical Society in Clifton displays a half dozen photographs of Shannon Copper Company mining operations on the walls. Freeport McMoRan still mines the Shannon incline where the Thompsons once held forth. You can see the operation from the state highway that cuts through the mining operations. I can’t tell you what a disappointment it was to see earth blasted, removed, crushed, and processed, which used to be the hallowed ground of this family operation. There ought to be a law! Just kidding.

Freeport McMoRan has done its best to remove traces of the past while it extols the innumerable economic benefits that mining brings to the region. The library in the new company town of Morenci might as well be a daycare center; children were the only ones there when I visited late one weekday afternoon. When I asked the librarian where the history stacks were, she said the mining company gave them to the county’s historical society. But I didn’t see many in my tour of the society’s museum, which is rarely open. In fact, the docent told me that the society did not have a library archive.

I did find some lovely pictures of Metcalf and the original town of Morenci that made me wonder what the hell is going on here. Many of the long-gone structures, including the schools, hotels, and government buildings, could easily have made it onto the register of historical places if they hadn’t stood directly in the path of progress. The Kruttschnitt home may not have been worth saving from an architectural perspective. But from my narrow family history perspective, it’s a travesty that I couldn’t return to the site of the seminal family gathering. The grainy pictures I have of them even evoke limited impressions.

A geological relief model at the historical society — I wish I had taken a picture of it — shows how things looked back in 1915 when the Shannon mine was going full bore. It even depicts the railroad route the Shannon Copper Company built to bring ore from the Metcalf mines to the smelters in Clifton. Shannon ran one of two smelters, which must have spewed considerable arsenic into the air in their day. In economics class, they used to call this an exigency cost.

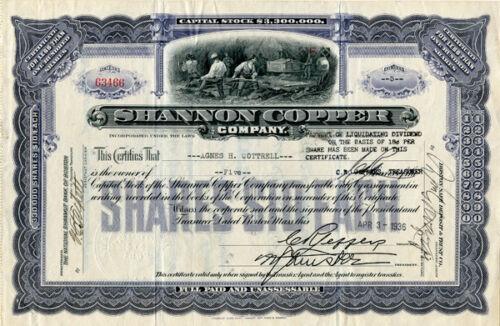

Thompson bought the Hughes and Shannon mine, considered one of the premier mines in Arizona, from Charlie M. Shannon in 1899. The deed on the mine was paid by a $2500 check drawn by Arthur Smith and signed by William Thompson, the father of William Boyce Thompson. The son later purchased adjoining claims from the Arizona Copper Company, the pioneer mining company in the district. The purchase gave Shannon control of 50 claims covering 400 acres, a 100-acre mill site, and some limestone claims on the Frisco River.

The underground mine workings reached 1,300 feet below the mountain crest. Two double-track tunnels ran through the mines, each 7 x 8 feet. At the mine entrance, the tunnels connected to a 1,400-foot, double-track incline tram that hauled ore to the railway. The tramway was inclined 36 degrees with six ore bins at either end and a retarding engine at the upper end. Ten-ton cars counterbalanced the tram. Steel cable passed around a 13-foot double drum that ran a small air compressor to generate power while serving as an auxiliary brake.

The Shannon mine initially relied on the Coronado rail line. Before long, Thompson determined that the company would be better off building its own railroad. The Shannon-Arizona Railway was initially capitalized at $600,000 and completed in 1910. The 10-mile line saved the company considerable money on ore haulage and provided some insulation from annual flooding. The 36-inch narrow-gauge railroad ran through 10 tunnels and over seven trestles, paralleling the Coronado along Chase Creek.

The Shannon line took ore to the company’s 500-ton concentrator on the San Francisco River, eight miles from the mine. The concentrator had ore bins 100′ long, in two sections, for first and second-grade ores. It treated about 400 tons of ore daily. According to one report from the time, the tailings carried as high as 12 percent copper. The concentrated ore was then taken to the 1,000-ton smelter at Clifton, which had two 350-ton water-jacket blast furnaces. An electric triplex pump pumped The water from wells near the San Francisco River. The smelter operated in connection with a small sampling mill.

The concentrator initially had trouble with acid waters eating iron screens in the jigs. It tried brass and copper screens, but they were too rapidly by abrasion. Shannon engineers ultimately relied on electrolysis to improve yield. When a low-voltage electric current was applied to the jigs, the screen became a cathode in the circuit, drawing hydrogen from the water. That, in turn, attracted metallic salts, including freed copper. “The amount of ore smelted has shown an unbroken annual increase since the fiscal year 1904, while costs have also shown improvement,” read a mining report from the day.

Metcalf was a wild frontier town in its day, one of the wildest in the country. William Boyce Thompson’s biographer Herman Hagedorn described it as “a mining camp out of the story-books with its single street of gin and sin and a scattering of low houses up the stony slope. The trail to the Shannon ran up the creek under the gracious shade of an occasional cottonwood rising from the creek bottom, then turned sharply eastward and zigzagged upward at incredible angles over barren ground dotted with boulders. The mine lay under the very summit.”

“Along the eastern bank of the river the saloons were thick and up Chase Creek Canyon they stood door to door. Along that narrow street, men, women and horses were so thickly crowded of an evening that a rider could scarcely make his way through. Gambling was open and everywhere. None of the familiar details of frontier mining camps was absent. The covered sidewalks, the second-floor verandahs where painted Mexican girls posed alluringly, the slouching cowboys, the flashy gamblers. Clifton was prosperous and wide open, the days were hot and the evenings long. The harsh background of the heights and ridges roundabout gave it all an appropriate setting.”

Against this untamed background, William Boyce Thompson cooly conceived a plan to make a fortune for himself and his siblings. He developed the idea of putting the mining claims into a corporation. Then, he conspired with other large Shannon investors, including family members and close associates, to keep the stock off the market for a year and a half. The value of the stock rose from $2.50 to $10 a share after the company’s mines proved richer than expected. The move tied up his father’s estate for a while but dramatically improved the stock’s value. The Magnate netted $50,000 from the deal. In one year, he turned that money into $1 million through stock market investments when margin requirements were low.

Shortly before he died, Thompson in 1929 sold the Shannon mining operations to the Arizona Copper Company, along with its railroads and reduction works, for $600,000.